A taxonomy of migrations

This is the first installment in a series of blog posts on the topic of technology migrations. If you want to start from the very beginning, you can find an overview of the series and an index of the posts here.

A taxonomy of migrations

When we talk about migrations in the technology domain, we usually refer to the process of moving from one technology, system or way of operating something to another. Within this pretty broad definition fall quite a few things that look pretty different from each other, so there is a lot of space for sorting them out into various categories.

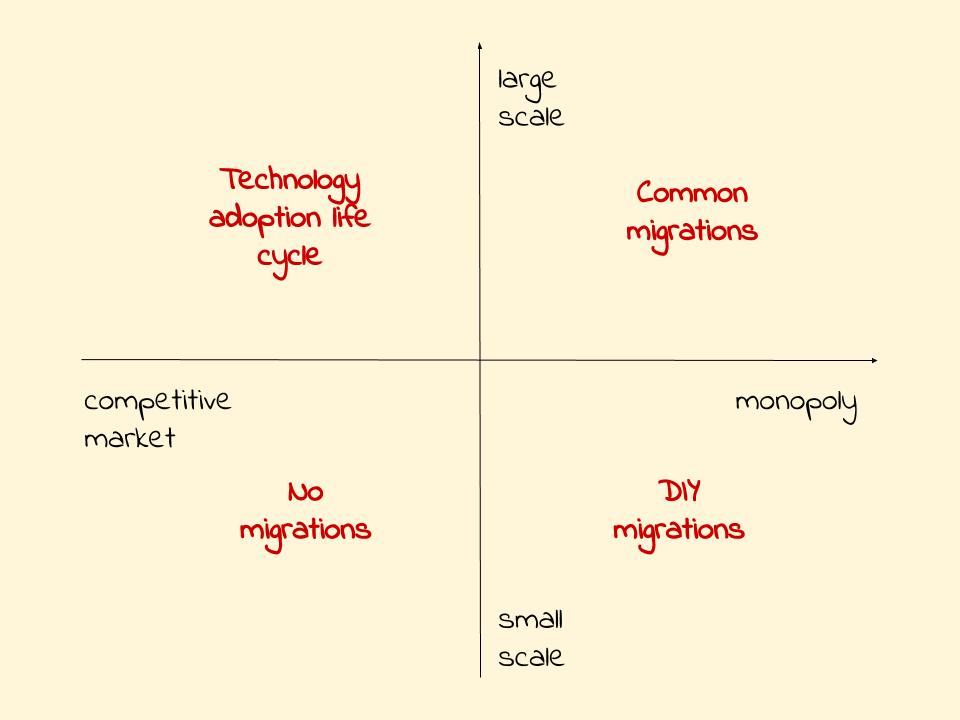

My personal taxonomy of technology migrations is based on two discriminants: market type and scale. Rather unsurprisingly, the scale axis goes from small to large, while the market type is on the spectrum between competitive and monopolistic. Other than the fact that I personally find it amusing, this classification helps me to communicate to others what strategy to adopt and whether to run a migration at all.

Migrations in a competitive market?

It is extremely rare to talk about “migrations” in a competitive market scenario. There are two good reasons for this. The first is that they are better known under a different name.

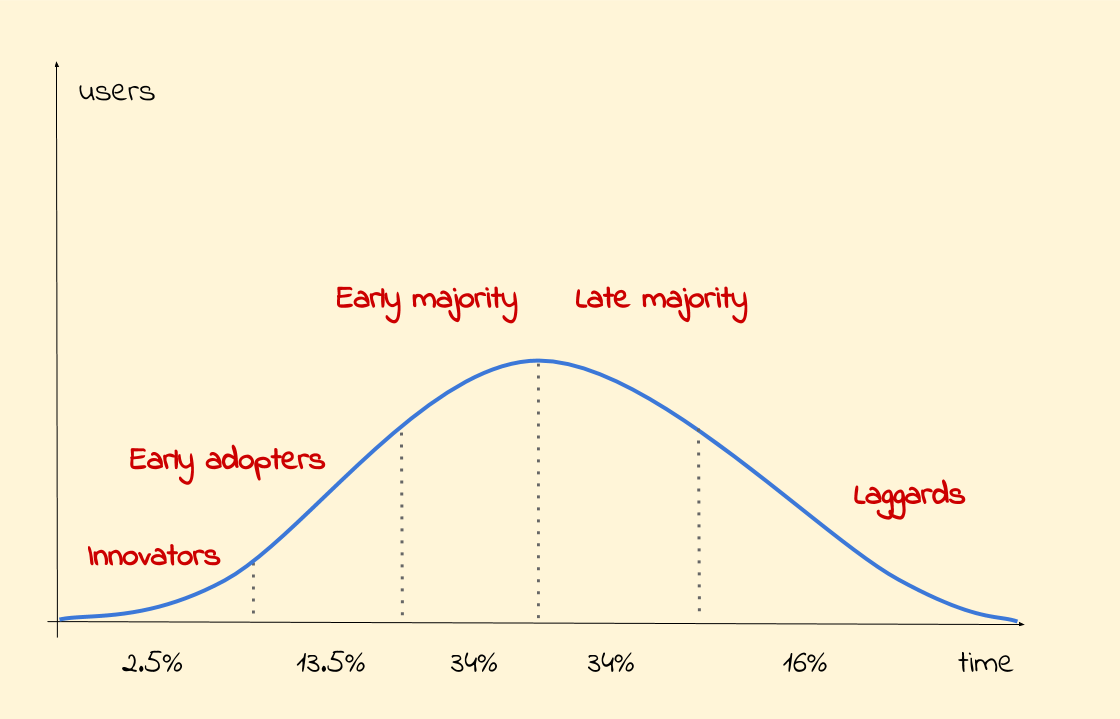

When we find ourselves in a competitive market (with multiple competing technology providers) on a large scale (like throughout a country or the world), I believe that migrations are largely described by the technology adoption life cycle. Yeah, exactly that one made famous by startups trying to show to investors how the world is going to react to their innovative product. Considering that the diffusion model it originated from has been used to track the purchase patterns of hybrid seed corn by farmers, we are definitely speaking about migrating from an old technology to a new one in broad terms An example closer to our times is the adoption of smartphones in the mobile phones market.

Although these are not the kinds of migrations we are likely going to be running in our career as software engineers (usually the players of this game are companies, legislators or communities), they are a fascinating domain that can be reasoned about in terms of economics, demography, networks, game theory and anthropology. I wonder if anyone analyzed the migration to Python 3 this way ;)

I am not going to cover the technology adoption life cycle in detail, as there is already plenty of literature about it. If you are interested, I recommend you start reading from the Wikipedia page.

Next is a competitive market on a small scale (like a company). I call this one the No-Migrations Quadrant because of the second reason why we don’t speak about “migrations” in competitive markets: we shouldn’t.

I believe that in such situations, instead of wasting time running several little migrations every time you gain a new user or use case, you should try to convince the people in charge that your technology is the best among all the ones available and that your team should have a monopoly over that technical area. The smaller the scale, the more forcing functions (e.g. management decisions) are effective as shortcuts to complete (or at least very large) adoption.

An example of one such migration that shouldn’t happen would be migrating the teams in your group from some in-house JavaScript framework to React, while another group is in the process of moving to Angular.

Migrations under monopoly

Operating under a monopoly, your team would have agency over what technology to adopt and how and when it should be adopted, and, at the same time, supply such technology. This doesn’t mean that your team should necessarily build such technology. At the time of writing, the trend in the industry is for internal teams to offer infrastructure and platforms by assembling and gluing open-source and/or commercially available solutions (e.g. a computing platform based on Kubernetes and AWS EC2).

What kind of monopoly would be best for your company to adopt is a whole different topic altogether. My default suggestion is to go for a “benevolent” monopoly, where your team is responsible for providing a “preferred” technology, but other teams are allowed to adopt something else if they can properly justify why that is a better fit to their use case. It might help to avoid the stagnation of innovation typical of monopolies, but only if your team is open to recognizing and taking ownership of new successful technologies that others may end up using. You’ll also have to be comfortable with some degree of chaos, of course.

DIY migrations

Moving on to the two monopolistic quadrants, things should start to look more familiar to most engineers in the crowd. When we talk about monopolies, scale is usually much smaller, so I tend to compare it to the capacity of the team.

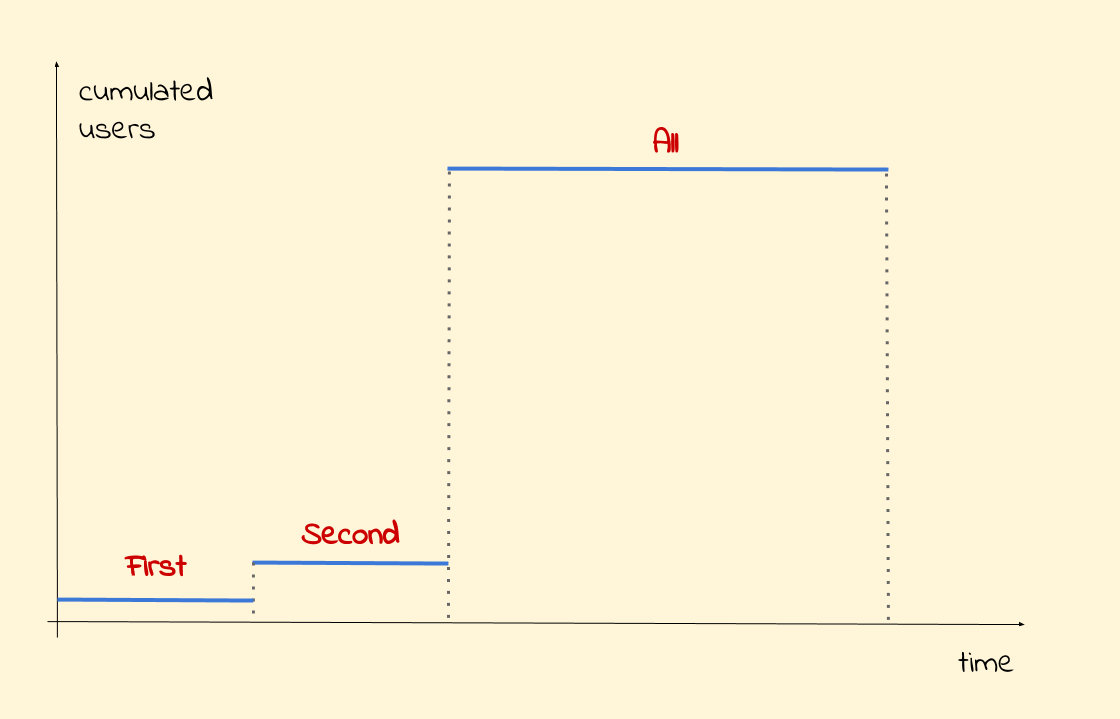

In the scenario of a monopoly on a small scale, your team could migrate all use cases by itself in a reasonable time. And it should. For this reason, I call the ones in this category DIY migrations. They are relatively easy to pull off even with minimal instructions:

- You migrate a first use case while perfecting your technology.

- You migrate a second one (or more) to make sure that everything works.

- You migrate all the other use cases (perhaps with the help of some automation).

A good example of this one would be to upgrade all services in your startup from Python 2 to Python 3.

When I suggest such an approach, new acolytes of migrations often look at me with wide eyes of disbelief. Changing other people’s code, deploying alien services, performing repetitive tasks: madness. You may well feel the same way; this doesn’t really sound like fun. It has one pretty damn good upside, though: little to no coordination required.

Coordinating with users, tracking down owners of legacy systems, persuading them to work on your migration instead of their priorities (or other migrations!), enabling and helping them to perform the migration, making sure everyone sticks to the deadline. Migrations rarely finish (or at least their length is highly unpredictable), because of the tremendous hidden cost of coordination. So rejoice: a little DIY can save you from the pain of herding human beings toward a not-so-shared goal!

Large-scale migrations

The last kind of migration is the one most professional software engineers are interested in: migrations under monopoly on a large scale (usually a medium-sized to large company). In terms of team capacity, this means that your team would not be able to perform the migration by itself in a reasonable time. This means that some degree of coordination with users is necessary.

If you are struggling to understand whether your case falls in the DIY migrations’ category or in the large-scale migrations’ one, you are probably looking at a DIY migration. Like in the movies, you will recognize a large-scale migration as soon as you see it.

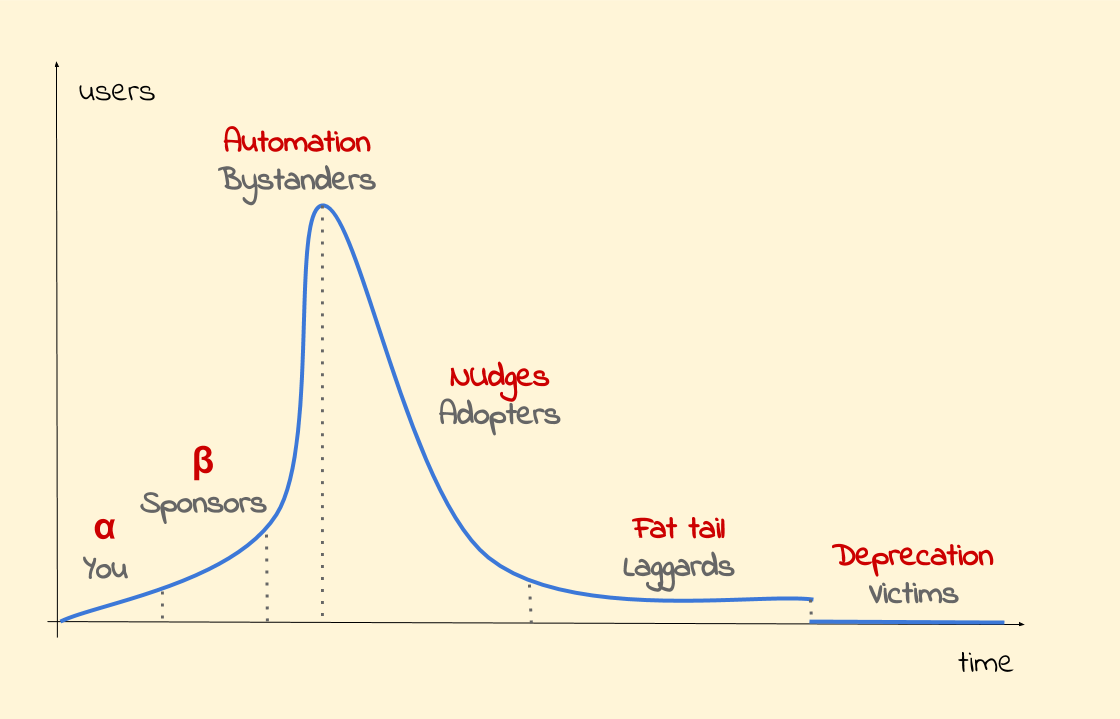

Inspired by the technology adoption life cycle, I came up with a personal psychographic representation of the users’ distribution over time for an “ideal” migration under monopoly (at least for my definition of “ideal”). I did it mostly for fun, I must admit. But perhaps this curve will make it easier for me to describe, and for you to remember, what happens during each phase of a migration.

Please note that the Y axis represents the number of users who migrated at a given time, not the total number of users who already migrated (which amounts instead to the area below the chart); this works exactly the same of the technology adoption life cycle chart.

If you are interested in this curve and in how to successfully pull off one of these migrations, follow me to the next post of the series.